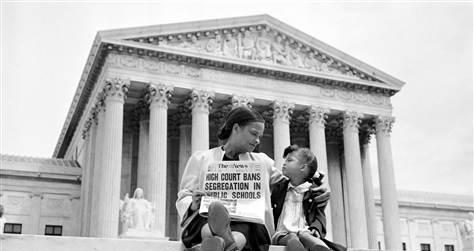

The Face of the Brown v. Board of Education Case, Linda Brown Dies

By Kaylin YoungMarch 28 2018, Published 3:43 p.m. ET

In 1954, Linda Brown was an 11-year-old girl whose parents just wanted her to have a quality education. In years to follow, Linda Brown would become the face of an educational movement that rallied for the desegregation of public schools and ushered millions of children of color into classrooms with their white peers. Over six decades later, on Sunday afternoon, Linda Brown died at 76 years old.

Before Americans marched for safe schools, progressive citizens marched for inclusive education. But Linda Brown did more than march. During her elementary years, Linda father, Oliver Brown, objected when he was told his daughter could not attend a public school in her neighborhood simply because she was not white.

Brown’s sister, Cheryl Brown Henderson recalled the day her parents’ request for their daughter’s enrollment was denied. In a video interview for History NOW, she said NAACP told her parents to “‘Find the nearest white school to your home and take your child or children and a witness, and attempt to enroll in the fall, and then come back and tell us what happened’.”

The school said no. So Linda walked a mile and a half to her segregated school. As she made her way through a rail yard, across a busy road and on a bus, Mr. Brown walked back to NAACP leadership to take the next step in repealing their rejection.

The case began with Oliver Brown, but ended with 13 overall plaintiffs suing The Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. In 1954, they won, but segregation in public schools continued for years. Until ‘The Little Rock Nine.’ In 1957, nine black students enrolled at an all-white high school in Little Rock, Ark. Their presence was met with racial slurs, physical torment and death threats. Those nine students had to be escorted onto the campus by federal guards so that millions of students of color could walk through school hallways, sit in a classroom and receive a quality education.

The Brown v. Board of Education ruling overruled the previous standard of “separate but equal” Plessy v. Ferguson decision in 1896, which allowed state-sponsored segregation.

Following the decision, Brown was enrolled in an integrated junior high school and went on to become an educational consultant and public speaker.

The supreme court ruling open integrated doors for students of color in more ways than one. A recent report by the Economic Policy Institute found that colorful classrooms was not the only advantage.

-“Over the last five decades, African Americans have seen substantial gains in high school completion rates. In 1968, just over half (54.4 percent) of 25- to 29-year-old African Americans had a high school diploma. Today, more than 9 out of 10 African Americans (92.3 percent) in the same age range had a high school diploma.”

“Over the last five decades, African Americans have seen substantial gains in high school completion rates. In 1968, just over half (54.4 percent) of 25- to 29-year-old African Americans had a high school diploma. Today, more than 9 out of 10 African Americans (92.3 percent) in the same age range had a high school diploma.”

In the 1950’s, black students were getting an education, albeit separate from whites, but an education nonetheless. However, the quality of their education was poorer; their books not properly bound; their schoolhouses not efficiently insulated. The Brown v. Board case gave blacks greater opportunity to prosper in academic settings.

When recalling her wintertime walks, Brown once said, “I remember walking, tears freezing up on my face, because I began to cry.” Brown’s tears, miles and perseverance are tokens of gratitude for today’s students of color who walk to class with students of all hues.